Guido A. Sanchez is a writer, middle school teacher and leader, comics aficionado, and podcaster based in New York. Guido revels in nurturing young people along their journeys as they begin to tell the myths of their own lives. Once the school day wraps up, he also steps into the role of cohost and creator of Dear Watchers: The Omniversal Comic Book Podcast. With his vast collection of over 30,000 comics, he navigates the intricacies, inspirations, and impacts of world-building in fictional reality and the modern myths we all love.

James Fenner is an illustrator living in Oregon but originally from the shores of Lake Huron in Michigan. James has a passion for editorial illustration, book covers, graphic novels and animated illustration.

I had the opportunity to interview Guido and James, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourselves?

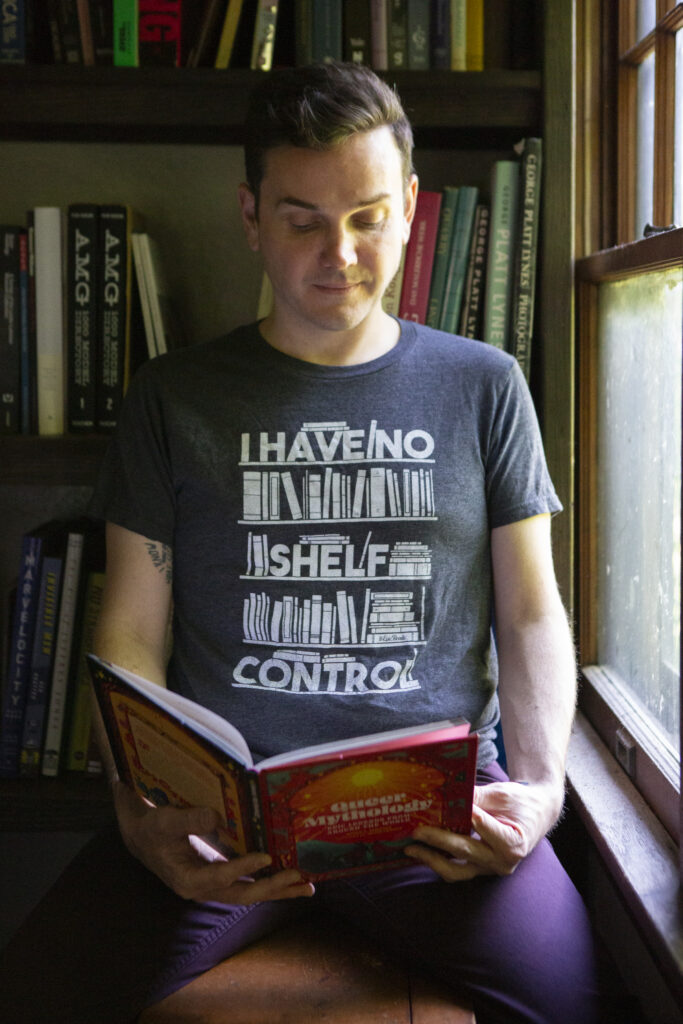

GS: Hey, I’m Guido—a middle school educator, comic book podcaster, and author of Queer Mythology: Epic Legends from Around the World. Before that, I wrote Spider-Man’s Web of Technology and a puberty textbook!

JF: I’m James Fenner, an illustrator living in the Pacific Northwest, but I grew up on the shores of Lake Huron in Michigan. I’ve always had people around me that encouraged me to pursue art & to live in my imagination.

What can you tell us about your book, Queer Mythology: Epic Legends from Around the World? What was the inspiration for this project?

GS: In many ways, this book has been in the making for my entire life. Growing up as a young queer person, I was drawn to all kinds of stories—myths, comics, video games, and even soap operas. Decades later, while working with my editor, Randall Lotowycz, it became clear that now was the perfect time for this project. It felt so obvious that a book like this should already exist—but it didn’t. After spending years working in middle schools, I was determined to create something accessible for readers of all ages. The inspiration, as I wrote in the introduction, is simple: we have always existed—in history and in stories.

JF: On my end the inspiration came largely from the cultures the stories derived from. I had to do a lot of research on visual representation through history. Many of the characters/stories had limited visual reference online, so I had to make sure I was staying as true to the source as I could. I also always enjoy pattern work, so I tried to use patterns in this book to help connect the cultures further to the artwork. Most of all, though, I wanted to make something that would have spoken to me when I was young. It’s such an honor to be a part of a book that presents so many conversations & ideas to a younger audience. It would have meant so much to me growing up.

How do you find and select each of the legends depicted in the book?

GS: I knew some of the legends simply from being a fan of stories and myths. However, even those I was familiar with often contained layers of queerness I hadn’t discovered before. I used academic texts as a starting point for research, digging deeper to uncover the oldest retellings I could find. While I don’t read ancient languages, I relied on early translations and worked to sift through iterations to get as close to the source as possible. For other legends, I explored specific parts of the world or historical eras to see what I could uncover. For instance, as a Cuban person, I was especially eager to include something rooted in Caribbean cultural traditions. As a Latinx person, I also delved into pre-colonial Mexican mythologies, which have such a rich history. My research spanned nearly every continent! Throughout this process, I focused on ensuring a diversity of religious stories as well, recognizing how central they are to many traditions. I wanted the book to include a broad and inclusive range of narratives.

What sources/books would you suggest for those interested in looking up more queer legends like the ones described in the book?

GS: A great place to start is Cassell’s Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol, and Spirit. But honestly, you don’t have to look far—queerness is woven into so many of these stories and traditions. Of course, how much of that queerness is visible often depends on who’s retelling the story, as many aspects have been erased or obscured over time. What I found most exciting during my research was realizing just how pervasive queerness is in these myths—not just at the center of the story, but often as a normalized part of life, for both gods and mortals alike.

Were there any stories you didn’t get to cover, but wish you could have?

GS: There were so many stories that didn’t make it into this volume—enough to fill a second one, which I’d love to create if this book resonates with readers! That said, there weren’t any I desperately wanted to include but couldn’t. There was one that almost made it: a tale involving Khonshu from Egyptian mythology. Unfortunately, I don’t have any Egyptian myths in this volume. It’s a tradition with fewer queer-centered characters, and Khonshu’s story, which involves his parents, presented a unique challenge. The narrative includes a dark act of violence at its core, and while I didn’t shy away from difficult truths in other myths, I wanted this collection to center joy—even with complex characters—and remain tonally accessible to all. Ultimately, the violence in Khonshu’s tale made it too difficult to adapt in a way that aligned with the tone and intent of the book, so I decided to leave it out.

JF: I don’t think there’s any specific story in mind for me, but after having friends & family read the book – I heard stories about indigenous Americans that I would love to make illustrations for, too.

As a creative, what drew you to the art of storytelling?

GS: I’ve been captivated by stories, characters, and worlds for as long as I can remember. This fascination is a big part of why I started my podcast, Dear Watchers, which explores alternate universes. World-building and the mythos created by storytellers—especially in serialized stories—have always drawn me in. As an adult and a Health Educator, I came to realize—and research backs this up—that stories have a unique power to shape people in ways that facts alone often cannot. Advocacy and awareness are crucial, but stories are what truly move people’s hearts and minds, and by extension, our culture. I firmly believe that stories don’t just reflect who we are—they also have the power to change the world.

JF: Art is my first language in many ways. It’s how I learned first to communicate with the world – drawing pictures before learning words. So, for me, storytelling is a necessity. It’s still how I process a lot of my thoughts/the world. However, storytelling is also an opportunity for others to see themselves in what you create. I think that’s a sort of subconscious & unifying magic. In this book, I hope I could visually help readers connect to the stories in a more whimsical way!

How would you describe your creative process?

GS: My creative process happens in fits and starts! When I was in school, I was a procrastinator, often completing papers—or even my entire thesis—in a last-minute burst of energy. What I’ve realized as an adult and a writer is that I was able to do this because I genuinely enjoy the act of writing. I’m not saying it’s easy to write well, but for me, the process of using language and committing it to paper or screen feels natural and fun. My brain is always turning over stories, so the initial draft is often like a brain dump—sometimes just a few sentences, other times a few pages. I write whenever inspiration strikes, whether I’m on the bus or dedicating a whole day to it. The real magic happens during revision. That’s where the process truly takes shape, evolving through refining, reworking, and, ideally, collaborating with others.

JF: My personal creative process is usually pretty intuitive. Your goal as an artist is ultimately to be your own favorite artist (not that you should ever achieve that). With that in mind – you follow what you find interesting, because only you can create that work. Creativity comes from your unique perspective – if you follow that, you’ll create something authentic & meaningful. For this project, I also built moodboards for each piece, compiling textiles/photos/clothing for each story. It’s a weird balance – I needed to look at other people’s renditions of the stories, but at the same time I had to know when to put it aside & make my own decisions. I had a lot of trust in everyone involved with the process to let me know if I was straying a bit too far!

What are some of your favorite elements of writing/illustrating? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or difficult?

GS: My favorite part of writing is discovering the essence of a story—figuring out what will hook a reader’s soul. It’s always unpredictable what will resonate, but I make it a point to understand the story’s meaning and purpose before diving into plot or characters. I also love editing. For me, it’s an exciting process of evolution, and I don’t feel overly attached to my words—they’re just part of a larger feeling I’m trying to create. This makes it easy for me to play with and refine them. What I find most challenging, however, is writing dialogue. Most of my career has been in academic or nonfiction writing, so finding the right voice takes time and collaboration. My husband has actually been a huge help with this! I’d often ask him for the corniest joke or pun he could think of, and I’d use that as inspiration for humor and dialogue that felt more authentic to the story. If you laughed at the sassy fortune-teller in Florinda’s story, that’s a great example of this process in action!

JF: I really see illustration as a vehicle for storytelling, so getting to connect with people & tell stories just through images is really magical. If someone can see my art & feel something – that’s the best part. Also, for me, it’s a form of meditation. However, that only happens once all the references/sketches are compiled. After I commit the references to memory, I put them aside and let my intuition take over – that’s always so much fun! The difficult part for me is always the technical side, so research in a project like this can be tricky. I’m an emotional sort of artist, so I need to find a way to connect with the piece/story on an emotional level. Thankfully, with a project all about queerness – I usually had a good ‘in’ for each character/story.

As creatives, who or what would you say are some of your greatest artistic and creative influences and/or sources of inspiration in general?

GS: I am inspired by anyone who is trying to tell a story. Truly, I’ll watch any documentary about art or storytelling and find myself moved to tears. Just this morning, it was a history of sitcoms—anything that explores the power stories have to shape us. Beyond the relationships we form with the people in our lives, I believe our souls, spirits, or whatever we consider our core, are fueled by stories. As a teacher, I’m inspired by those who are figuring out their identity, and I often draw on that creative journey as fuel for my own writing. Concretely, my storytelling brain has been deeply shaped by the prose of David Mitchell. His multi-layered, interconnected narrative in Cloud Atlas is, to me, one of the greatest storytelling achievements. I’m also profoundly influenced by the comics of Alan Moore, who challenges boundaries of thought through a blend of philosophy, magic, and superheroes—then shatters those boundaries to expand our minds. Lastly, Mark Gruenwald, who coined the term ‘omniverse,’ has inspired my sense of storytelling in countless ways, including the creation of my podcast.

JF: It is ever changing & I think it needs to be. You’re always trying to be a better ‘you’ as a creator, so those influences come & go. The constants for me are my experiences/observations of the world around me. Paying attention to how a place/experience made me feel & assigning meaning to those places is something that I really prize. For specific creators, David Lynch has always been a huge influence. For just illustration, artists that I keep turning to for inspiration are, Sterling Hundley, Sam Weber, Jillian Tamaki, Jon Foster & Tomer Hanuka. I’m an illustration-nerd, though, so I could keep listing names until the end of time!

Aside from your work, what are some things you would want readers to know about you?

GS: I mentioned that I co-host a comic book podcast about alternate universes, Dear Watchers, with my husband. We’ve recorded over 150 episodes, drawing from my personal collection of more than 35,000 comics. That’s a fun tidbit about me! I’m also an avid collector of ephemera—everything from paper and magazines to VHS tapes and mixtapes—especially items tied to queer history. These collections reflect my passion for preserving stories and pieces of the past that might otherwise be forgotten.

JF: I think, because I usually draw dark & dreamy sort of things, some people assume I’m sort of that way, too. That’s true, but I’m also a perpetual optimist & goofball. I think it’s important for creators to take their work seriously, but to never take themselves seriously.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet but that you wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

GS: What makes writing for kids unique? This is a question I wish I’d been asked, especially because I’ve been thinking about it while reading Sam Leith’s The Haunted Woods, a brilliant survey of children’s literature throughout history. One point Leith makes resonated deeply with me—so much so that it clicked into place retroactively after I finished my book. When you write for young people, you’re not just writing to them. You’re also writing to the adults in their lives who might share those stories with them, and, perhaps most importantly, to the child you once were. I love this idea because it captures something I now realize I was doing instinctively: speaking across time and relationships, creating stories that connect generations and reflect the way stories shaped me when I was young.

JF: “What advice would you give to other queer people potentially just discovering themselves?” As queer people, we have the benefit of self-reflection (and often the burden of self-doubt). I didn’t come out until quite late, but everyone around me knew long before I did. Since then, I’ve found so many of the ‘certainties’ I believe about myself to be proven wrong over & over again. It is so liberating to let go of the boundaries & boxes you put yourself in. Circumstances & context change everything, so I encourage you to put aside some ‘certainties’ you feel about yourself and allow yourself to be more flexible.

What advice might you have to give for aspiring storytellers out there?

GS: My biggest advice for aspiring storytellers is this: network. It might sound crass, but it’s true—so many of the opportunities I’ve had, both creative and otherwise, have come about because of relationships. Of course, doing the work is essential, and you’ll hear people say to keep writing, embrace failure, and build perseverance. That’s all valid, but the truth is, our world thrives on relationships and connections, for better or worse. Get yourself out there and connect with people. This project, for example, started because I invited a guest onto my podcast, and what followed was an unexpected synergy—almost like falling in love—that led to collaborations and ultimately a friendship. You never know what kind of creative doors will open just by making connections with people like you.

JF: I know I said it above, but it’s a mantra I try to remind myself of – your goal as an artist is to be your own favorite artist. Only you can create work specifically made for you. Based on your favorite colors, places, moments, places, etc – let influence come from everywhere. Do you have a specific cup that you use for coffee every morning? Draw that into your artwork – that’s a unique cup only to you. Maybe you have a specific tree that’s special to you? A favorite stone you picked up on a beach? By compiling all of those things together you’ll end up with your own style in no time. Don’t fight that, lean into it. Pay attention to the things that capture your attention & use those as fuel for your creative fire – whatever form that takes. I would have found my style so much sooner had I not fought it so hard!

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

GS: My editor from Queer Mythology currently has about a dozen of my book ideas on his desk, so there are plenty of potential projects—almost chaotically so! The one I’m focusing on first is a way of telling queer stories from history but with a unique twist, this time weaving in an ancient framework that is a bit like mythology—but that’s all I’ll reveal for now. I’m also always open to the idea of a follow-up to Queer Mythology! In the meantime, I write a part-queer history, part-storytelling Substack called The Substrate, and you can catch me every other week on Dear Watchers, my omniversal comic book podcast.

JF: My husband & I are just about to embark on the Shikoku Pilgrimage in March through May. It’s been a lifelong goal to walk it. You circle the island of Shikoku & visit 88 temples along the way. I’m not exactly sure what I’ll create when I return, but keep an eye out for it! Aside from that, I have two personal graphic novel projects in the works. One especially deals with queerness & the self-discovery that comes along with that – can’t wait to share more of it!

Finally, what queer books/authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

GS: I’m certainly not the only one to say this, but everything James Tynion and his collaborators are doing is extraordinary. The name of his company, Tiny Onion, is so fitting—the layers in each of his stories are fun to peel back, and there’s truly something for everyone. I also have to shout out Sacha Coward’s Queer As Folklore, which was released around the same time as Queer Mythology and makes a perfect companion.

My editor, Randall Lotowycz, has created some fantastic and essential books about comics, including The Superhero Playbook and The DC Book of Lists. Finally, I have to highlight my amazing collaborator, James Fenner. He recently worked on a major press comic as a colorist, and his art is some of the most outstanding I’ve seen—he’s absolutely a visual storyteller to watch!

JF: I don’t read books as much as I would like to, but I’d love to shout out some great queer books I’ve worked on recently; Someone You Can Build a Nest In by John Wiswell & We Mostly Come Out At Night by Rob Costello.

0 Comments