John Wiswell is a disabled writer who lives where New York keeps all its trees. He won the 2021 Nebula Award for Best Short Fiction for “Open House on Haunted Hill,” and the 2022 Locus Award for Best Novelette for “That Story Isn’t The Story.” He has also been a finalist for the Hugo, World Fantasy, and British Fantasy Awards. His fiction has been translated into ten languages, and has appeared in venues such as Uncanny Magazine, the LeVar Burton Reads podcast, Tordotcom, Nature Magazine, Lightspeed Magazine, and the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

I had the opportunity to interview John, which you can read below.

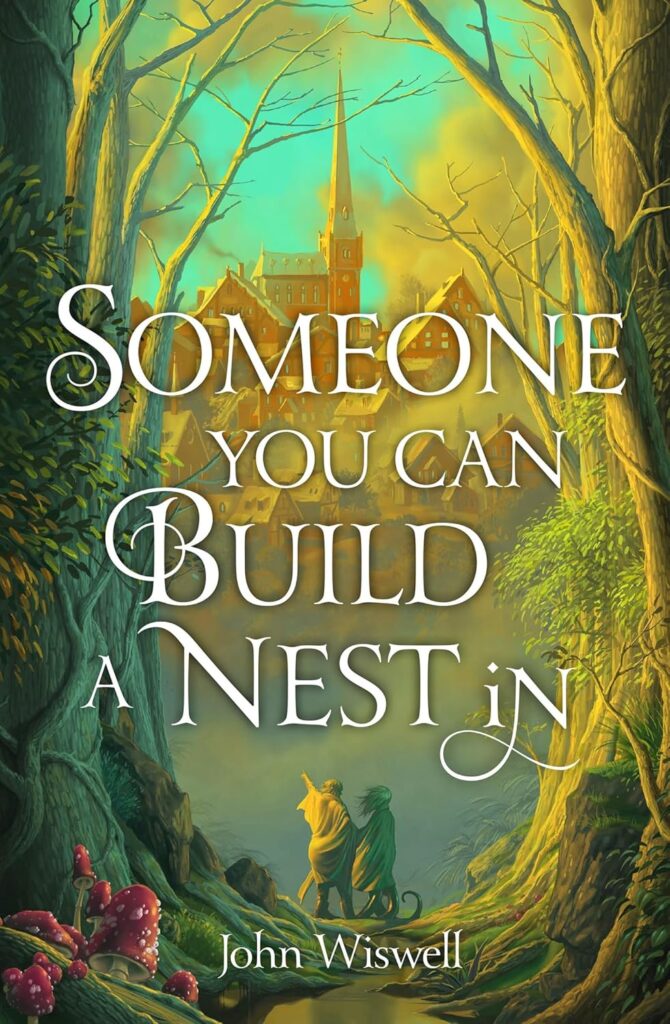

What can you tell us about your debut book, Someone You Can Build a Nest In? What was the inspiration for this story?

Someone You Can Build A Nest In is the story of Shesheshen, a shapeshifting creature who’s made the mistake that’s fatal to all monsters: she’s fallen in love. After being driven from her lair, poisoned, and driven off a ravine, she thinks she’s finally been slain. But she’s rescued by Homily, a kindly stranger who mistakes Shesheshen for a fellow human. Homily nurses Shesheshen back to health, and the two of them grow increasingly close as they find they have a lot in common, especially surviving in the wilderness. The closer they get, the harder it is for Shesheshen to keep her secret. She’s about to confess when Homily reveals why she’s here: she’s hunting a horrible shapeshifting creature. Has Shesheshen seen it anywhere?

And honestly the inspiration? It was the two of them. This story existed in two states: it was a funny idea about a flesh-eating monster having a crush on a cinnamon roll and trying not to blow it—and then it was a full blown novel exploring the pain they’ve carried their whole lives and trying to bring better things out of each other. It was about disrupting monster hunting, and seeing things like queer-coding and disability-coding in monsters as an invitation to empathy rather than otherness. I love monsters and I wanted to share a bit of why.

As an asexual person, I was excited to hear that Someone You Can Build a Nest In explores themes of asexuality and disability/neurodivergence in your book. As a queer, disabled author, what did it mean for you to put this kind of intentionality into your work?

It was liberating. I’ve been publishing stories for fifteen years, but for most of that time I felt like those parts of my life weren’t welcome in stories. That the world didn’t want to see us. The longer I wrote, though, the more queer people I met, and disabled and neurodivergent people, who hungered to see themselves at all. Realizing how many people were hungry like myself is what got me to write like this.

And yet I’ve never written a character who was so open about her neurodivergence as Shesheshen. She masks in socializing, but not in how she relates her truths to the audience. We get to feel how she does, in the ways she does. After decades of hearing that neurotypical readers couldn’t sympathize with a neurodivergent character? I’m happy to report that neurotypical readers are way cooler than that.

You mentioned intentionality, but it was also about intersectionality. That we who think differently may also question gender, question sexual attraction, or how we present our bodies. That characters can have multiple complications that give them a different experience of walking through the world. And in Shesheshen, I met a protagonist who had absolutely no shame about it. She rejoices in what she is.

As a writer, what drew you to the art of storytelling, specifically speculative fiction?

When I was a kid, I was bedridden by illness. Suddenly I was in inexplicable pain all of the time, and on many nights I couldn’t sleep. The only thing that got me through many of those brutal nights was the allure of a good story, and wanting to know what happened next in some book by Stephen King, or Mark Twain, or J.R.R. Tolkien. I’ve been in love with storytelling ever since. But as I grew up, I also wanted to write stories that could do for others what stories had done for me. If my book makes someone less lonely for one hard night, then I’ve done my job.

How would you describe your writing process?

I’m a creature of excitement. All I need is for one element to stick out to me–some funny worldbuilding quirk, or a juicy inciting incident, or in the case of this novel, a relationship dynamic. I was so drawn to Shesheshen and Homily’s powerful but vulnerable dynamic. It was at once funny and deeply heartfelt. Would the monster blow this? Would the hunter ruin her life by catching her prey?

Once I have a bit like that stuck in my head, I obsess. I spin out context. Shesheshen is isolated and angry, but what life experiences made her that way? Homily is caring and so willing to sacrifice herself, and what plot complications will that make? Who else is in their lives, and what lasting impressions have they left? It’s like being trapped in the orbit of a story. I love this phase.

Eventually I knock out a short plot skeleton. Someone You Can Build A Nest In was maybe ten or fifteen plot beats long. There were key events that I thought Shesheshen or Homily would make powerful, and the plot would build to them. With the plot skeleton as a loose guide, everything else is writing the flesh onto it, until it’s a living, breathing book. So I guess my writing process isn’t so different from my monster!

Growing up, were there any stories in which you felt touched by/ or reflected in? Are there any like that now?

I wish I’d seen more asexual representation as a kid. Or really, I wish I’d heard it was a possibility in the first place. The only figure who I knew of who was treated as “okay” to not be in a relationship was Jesus Christ, and that’s a funny queer role model. The first explicitly ace figure I can remember was Lloyd Asplund in Code Geass, this tech genius who would rather build big robots than pay attention to the arranged marriage he got stuck in. It was fascinating, seeing that modeled without shame. He was just going to pursue his joy. Ace folks aren’t joyless automatons. But we can enjoy building them!

As a writer, who or what would you say are some of your greatest creative influences and/or sources of inspiration in general?

I love to read nearly as much as I love to write, and the greatest privilege to publish right now is that I get to be peers with brilliant people like Arkady Martine, Aliette de Bodard, Isabel J. Kim, Eugenia Triantafyllou, Sarah Pinsker, and Vajra Chandrasekera. I saw a photograph of my book on a store table beside Kelly Link and Ted Chiang, and just looking at the photo, I had to sit down. We’re all part of a storytelling community together. Seeing what others do pushes me to experiment. To write truths that I didn’t think could be expressed on the page.

What are some of your favorite elements of writing? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or difficult?

The fastest way to make me care about a character is to have them care for somebody else. Fighting for yourself can be valiant; fighting to defend your kid, or your sister, or your best friend? That’s when I come to love someone. So in writing, one of my favorite things is finding the unique way they connect with somebody else, and how that relationship changes what they want out of life. It changes what you’ll sacrifice. It chances who you are.

As far as the most frustrating things to write? Whatever doesn’t fit. If it feels like the story doesn’t need it, or if it distracts from what the story is actually about, I’ll drag my feet. But sometimes you have to write those things to see what was missing all along.

Aside from your work, what are some things you would want others to know about you?

I like puns.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet but that you wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

Why don’t people eat watches?

Because it’s time-consuming!

What advice might you have to give for aspiring writers?

There’s so much I wish I’d known when I started out. You have to finish things, just so you get used to your habits of making entire things. You need to work a lot before you develop habits. Don’t wait for a brilliant idea; write ridiculous ideas if they’re all you have, and follow what excites you, because even if this project isn’t what breaks out for you, it’s practice. Hone your skills so that someday when you get to the right project, you’re ready to meet it head-on. And if you’re nervous about that, then start in shorter projects, and make sure each one does something different. This story pushes comedic dialogue; the next sets up a clever twist ending; the next expresses something about your dating life you’ve never seen fiction do before. By testing yourself that way, you expand your toolkit. You’ll be surprised how quickly your skills will grow. You’ll tell stories that right now, today, you think you can’t pull off. Trying and failing are just little steps. You’re the destination.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

I’m putting the finishing touches on my next short story, which will drop at Reactor this summer. “I’ll Miss Myself” is the story of an app that shows posts from every other version of yourself in the multiverse—and about the secrets the app has been keeping from all of you.

Finally, what books/authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

How much time do you have?

Isaac Fellman is a fascinating voice who immediately springs to mind. My favorite novel of his is Dead Collections, about a trans vampire who just wants to spend his life in the safe, dark archives, preserving ancient books.

L.M. Sagas just published her debut novel, Cascade Failure, which is like a much queerer Cowboy Bebop.

Ioanna Papadopoulou’s Winter Harvest is a great retelling of the myths of Demeter.

S.L. Huang’s Water Outlaws is a must-read for anyone who enjoys the Chinese classics, a retelling of The Water Margin from a bold queer lens that seeks to unerase people who otherwise wouldn’t be acknowledged in the face of war.

It truly is a wonderful time to read.

0 Comments