Noah Whiteman is an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is Professor of Integrative Biology and of Molecular and Cell Biology. At Berkeley, he is also affiliated with the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, Center for Computational Biology, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Jepson and University Herbaria, and Essig Museum of Entomology. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020 to write Most Delicious Poison and lives in Oakland.

I had the opportunity to interview Noah, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

Thanks so much for the opportunity to share my story and the story of nature’s toxins with you. I’m a professor of evolutionary biology at UC-Berkeley, and more importantly, a son, brother, uncle, and husband. I’m originally from northeastern Minnesota.

Given that your organization is all about being a “Geek” and being “OUT!”, I thought it might help to share what it was like to be a “Geek” and “OUT!” in the early 2000s in the U.S. when I came of age as both a queer person and a scientist. This might help your younger readers in some way given how difficult the social and political environment has become for queer people again in the U.S.

My family lived in Duluth, Minnesota from when I was around 3 to 10 years old. Duluth is situated along the north shore of Lake Superior. We then moved about an hour’s drive north, to a more rural part of St. Louis County near the Sax-Zim Bog where I went to a K-12 school that had less than 200 people total (and is now closed). My parents sold furniture and didn’t graduate from college, so I was the first to do so in my family. I was surrounded by nature growing up and fell in love with it. I became a naturalist at a resort near Grand Marais at the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in the summers during college—teaching people how to canoe and about the plants and animals of the boreal forest.

I was not “out” in high school or college, but when I moved to St. Louis in 2000 and met the man who would be my first boyfriend, I finally came out at the age of 24. This was during the George W. Bush presidency, who built his candidacies around opposing the fledgling civil union/marriage equality movement and used it as a wedge issue to get elected–his reign was deeply revealing of the power of political dynasties in our country, the flaws in our election system, and the power of money in politics. His reign was personally demoralizing—but it was also a good lesson in hindsight—it taught me that self-esteem, and yes, pride, must come from within, not without. However, I found that pride was cultivated by surrounding myself with other queer geeks and people from all walks of life who lifted me up and accepted me for who I was. For me, this included joining Front Runners, a queer running group, and building community with the other graduate students in my Ph.D. program at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who were mostly studying tropical biology and mostly from Latin America. That academic community in St. Louis, which included mostly straight, cis people, was a shelter in what was a storm for queer people in the early 2000s in the U.S. Queer culture was not by any means mainstream then and was centered on queer neighborhoods like the Castro, Boy’s Town, Chelsea, etc. in the larger cities of the U.S. and in the gay/lesbian bars in St. Louis and even in some of the smaller places. Something was gained when queer culture went more mainstream and was seen as an untapped market for corporations and politicians, but something was also lost. There remains a tension between the queer civil rights movement and the monetization of queer culture by corporations, non-profits, and political institutions. While there have been many positives, there have also been many negative consequences, because corporations exist to make money, non-profits have their own agendas that may be at odds with queer civil rights, and political institutions exist to promulgate political power in concert with the former two, and so each can be a fickle and unreliable partner in the fight for equality. In the end, building community is what really matters—I am skeptical of heteronormativity in many ways, even though I am really “trad” in many ways—the tension I describe as problematic (between heteronormativity, social acceptance, and the anti-establishment nature of queer culture) exists within me too.

Like all 20-somethings, the social and political milieu around me shaped who I became as a person, even if I wanted nothing more than to be left alone, just do my science, be a geek, and teach others what I had learned. It was confusing because while I didn’t have the same rights as others and was deprived of opportunities in some critical ways, I also had the privilege of being a graduate student pursuing a life of the mind and doing field work in the Galapagos Islands with researchers from around the world and then becoming an NIH-funded postdoctoral scholar at Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital. Such are the dualities in my country, which I deeply love in many ways, but also find deeply disappointing in terms of some of its policy. So, I saw science as a great path and escape from the political maelstroms that were draining and, in the end out of my control and simply not my passion. However, I didn’t know many queer scientists then, especially at the upper echelons, and although there are many more queer junior scientists and a growing number through the ranks, there are exceedingly few at the top, still. For example in one of my departments of around 30 full time faculty at UC-Berkeley, I am the only “out” faculty member who has a main appointment in the department to my knowledge. This tells us a lot about the overall social conservativeness of academic STEM despite the individuals therein being largely thought of as at least leaning “liberal” in the political sense—it is a fundamentally hierarchical system that is by its nature slow to change. Having said that, I have grown to love my Berkeley campus and feel strongly supported by my faculty colleagues and our leadership—I feel free be both my full “Geek” self and my full “OUT!” self. But it is our students, many of whom are first generation college students like me from low socioeconomic strata, who inspire me the most. The UC-Berkeley students are in general, earnest, highly ambitious, intelligent, and kind. They give me great faith in the future and yet they are not monolithic in any way despite what some like to think—and this diversity is inspiring to me.

In the 23 years since I came out, the situation has improved for LGBTQ+ people in the U.S. in fits and starts, and more gradually in academic STEM as well, but it has recently taken several very large steps back, owing to how queer, and particularly trans and non-binary people are being scapegoated, again, by the same political machine that stoked divisiveness against queer people when I was a doctoral student, and long before. The situation is heartbreaking to witness.

I should note that I am unaffiliated politically and relate all of this to you in my personal capacity and not as an employee of the University of California or in any of my other professional roles.

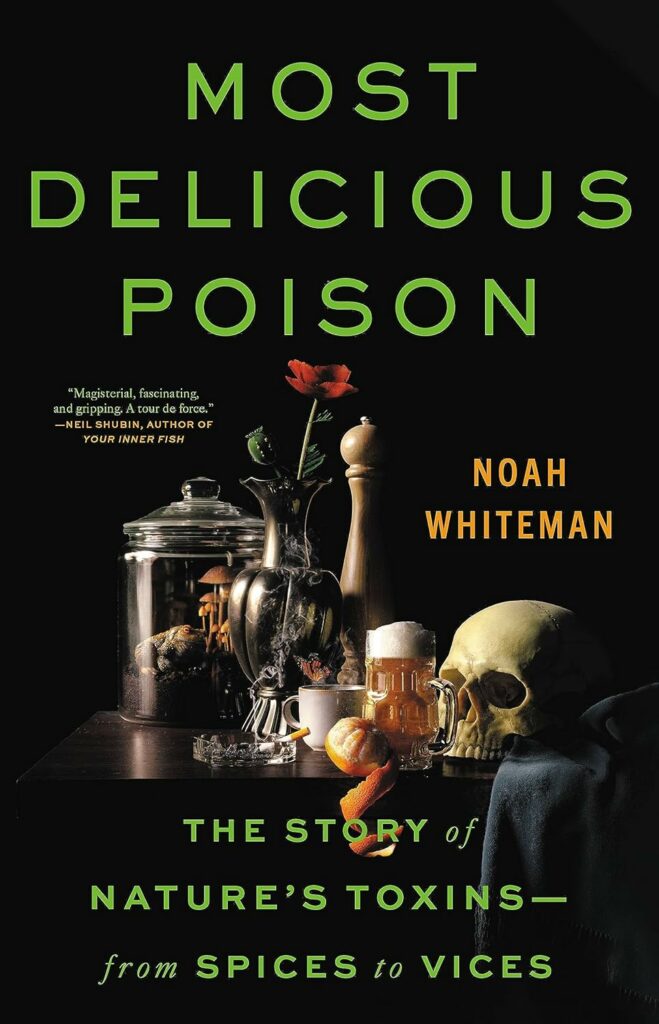

What can you tell us about your upcoming book, Most Delicious Poison. What was the inspiration for this project?

I am so excited to share that my book Most Delicious Poison will be published on October 24, 2023 by Little Brown Spark (a Hachette Book Group)—although you can preorder it now (visit: https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/noah-whiteman/most-delicious-poison/9780316386579/ or www.mostdeliciouspoison.com). Through an introduction and 13 chapters, I illuminate where many of the strange, natural chemicals we use in our food, drink, medicine, spiritual practice, and in recreation come from (mostly plants), why they evolved (largely as chemical defenses against attack by animals and pathogens) from the perspective of adaptation, how many animals have evolved mechanisms for overcoming them (think The Very Hungry Caterpillar) and even use them for their own devices, and how humans have done the same. I then trace how certain chemicals have played an outsize role in human history and even my own life. For example, modern surgery became possible owing to toxins from plants first used by Indigenous peoples of South America (tubocurarine in curare arrow poison and cocaine in coca leaves). The pursuit of spices by Europeans in the 15th century forever changed the trajectory of humanity, led to the Opium War, and even shaped the outcome of World War II.

The inspiration for the project was the collision of two worlds I had long kept separated—my own research on the origin of nature’s toxins and how animals overcome and use them—and my father’s long struggle with alcohol use disorder. The alcohol that we drink is ethanol that is produced by yeast as a kind of ‘private reserve.’ This substance, when diluted quite a bit, allows them access to form of energy that is also toxic to other organisms. Humans can also use ethanol as an energy source, but of course it is also toxic at even relatively low doses. Some people, particularly those who were victims of childhood neglect and abuse, are more likely to turn to drugs like ethanol as a way of coping and my dad fell into this category. His death at age 69 from complications of alcohol use disorder in 2017 came on the heels of work in my lab that was sort of reaching its zenith on the how the monarch butterfly used toxins from its milkweed host plants to defend itself. To reconcile these two spheres of my life, I was inspired to write a short proposal to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and was shocked to have been selected for a fellowship in 2020. This led to a full-fledged book proposal and, eventually, the book itself.

As a writer, what drew you to the art of storytelling, particularly non-fiction?

I think humans are all storytellers—long before we had written language we had stories—this is how most information was moved from one generation to the next. So, we are adapted to do it and I am just riding that ancestral wave that continues to reverberate through each generation. However, my first summer job in college was as a naturalist and telling stories about nature, summing things up without leaving out important details, became an art I had to master. I enjoyed doing it. I think being a professor is similar—I have students for only 50 minutes at a time in my evolution class and have to impart the really salient points in a way that will have a lasting impact. This is also challenging and something I’ve become better at with practice. So, I feel like I was ready to take on this project. I’m also 46 years old, and I feel like I’ve accumulated enough experiences with nature and in scientific discovery to tackle something big. I am a consumer of all kinds of non-fiction, and this has been true since the day I could read (or be read to—according to my mom!). I feel like I am just a vessel through which the natural world can be revealed to others—I see myself as a journalist covering what Charles Darwin called “the war of nature” and my job is to report it in a way that is engaging and factual, and maybe inspiring. The difference with true journalism is that while journalists shouldn’t ideally be part of the events that they are covering in a direct sense, humans are part of nature, including the difficult parts. We are not separate from nature even if we leave the planet an colonize the moon or Mars—we will take our microbes, crop plants, and own bodies with us—which all encompass 4 billion years of evolution of life on Earth. Plus, I am a scientist first and foremost, and so what I report I am also professionally and intellectually embedded deep within.

As a scientist, what attracted you to biology, and specifically this area of study?

It was my childhood ensconced in the boreal forests of northeastern Minnesota coupled with my father’s love of nature. All of that is so deeply imbued in my identity that I cannot imagine not being a biologist now. However, when I was younger, I had no idea I could be a biologist until late in college. It was then that I did an honor’s thesis and it focused on adaptations between insect species that arose through competition between them for resources—something called character displacement. I then focused on insects for my M.S. degree and on co-evolution between parasitic insects that attacked the Galapagos hawk for my Ph.D. For my postdoctoral research, I wanted to focus on insects that attacked plants because I was so enamored with plant diversity and so I did that through an NIH fellowship at Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital for three years on how plant toxins protected plants from their enemies, and how the enemies can sometimes overcome them and that’s what I continue to study today. We also now have a project on the evolution of foraging traits in hummingbirds with collaborators at Princeton University and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory. Hummingbirds are honorary insects in my mind!

How would you describe your creative process?

For me, I need to be alone to get the flow going, but not necessarily in some exotic or really secluded place. What I really require is time. Time to think, including meditative walks, runs, or stake skiing trails in nature allows for connections to be made in my mind that would not appear otherwise. I have had moments of realization that occur during exercise that are more profound than those that occur when I am sitting at my desk working. I tend to get obsessive about a particular topic and so having time to fall down the rabbit hole is essential to my process. Having a supportive husband who is also highly creative and introverted in his own right helps too! We both like our solitude and quiet environments in which to work.

As a creative, who or what would you say are some of your greatest creative influences and/or sources of inspiration?

Nature is my greatest inspiration, both what I observe and what I can find in the literature—that is—nature filtered through the minds of other people (scientists mostly). Traveling is also inspiring because it allows me to see how people from different cultures have interacted with nature, tried to harness it, escape it, define it. Art museums help in this way a lot because they are time capsules of what it means to be human. A person who is greatly inspiring to me in important ways is Alfred Russell Wallace, the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. He was not landed gentry and struggled to “make it” in science—he did make it though, through great tribulation in South America first, and then in what is now Indonesia. For him, as it was for me, traveling and studying natural history was transformative. We just use new tools now to study layers he couldn’t see in the 19th century, but we are doing the same thing as evolutionary biologists now—trying to understand how life came to be and in the end, how we as humans came to be.

Growing up, were there any stories in which you felt touched by/ or reflected in? Are there any like that now?

The book that made a lasting impression on me as a child is “Pets in Jar” by Seymour Simon. The primary reason for this is that the illustrations were just superb and many of my favorite animals were covered, including the monarch butterfly, which I have now studied myself! What I liked about it was that the animals were small and the point was simply to be able to easily observe their behaviors in a mason jar. As I got a bit older, I began to read more fiction, although it was difficult for me to finish novels. But when my friend and I read Macbeth together, though, it was transformative in so many different ways for me—it might have been that by reading it with her made it feel more alive and it forced me to follow through with finishing it. When I got to college, being at a liberal arts college in Minnesota (Saint John’s University and the College of Saint Benedict) also forced me to read widely and deeply, especially fiction but also some non-fiction, in courses I took that ranged from East Asian History, the French Revolution, to Peace Studies and the Philosophy of Human Nature. I took a January Term course just on the works of Albert Camus from a philosopher and in another year I took a course on Cosmology and the origin of the universe from an astronomer. This classic liberal arts experience was actually the most important in training my mind to think synthetically, which comes naturally to me, but I needed to be forced out of my comfort zone of the natural sciences. I believe that by not being able to take all of the natural science courses I wanted was a blessing in disguise—sometimes we don’t know what is best for us in a narrow sense—which is why course requirements that cross the disciplines are so important to maintain at the university.

What are some of your favorite elements of writing? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or challenging?

I love to write—it is not difficult for me. Good writing, however, is difficult, as it is for everybody else! Good writing must involve the perspective of others—especially trusted confidantes and editors. I like the process of both the first pass and of revising my own text, of honing in light of my own internal criticism and that of others. I love the research element too, the falling down the rabbit hole and the feeling that comes with it of being totally immersed and frankly distracted from everything else going on in my life and around me that it precipitates. The most challenging to me is coming back weeks or months later to revise again something I wrote. Picking up the threads where I left them off can be challenging, even boring, but it must be done. At the risk of using yet another metaphor, an essay, a book, a presentation, is like a block of marble—there is a vision of a beautiful sculpture there in one’s mind—but it takes many large and small strikes of the chisel to get there and even when it is done—there is the realization that the next one should be done a bit differently.

One of the hardest parts of writing a book is finishing one. Were there any techniques/ strategies/advice that helped you finish your first draft?

I worked on the book manuscript religiously for one year, as I would my main scientific work. I also continued my main scientific research, so I was doing double-duty. This was not sustainable for more than a year. However, it helped that I thought of it as an extension of my primary scientific research, and although I knew it wasn’t a scholarly book, I did know that it would be an instrument through which I might be able to share my passion for natural history and evolution and therefore teach people a bit about both. I also had terrific editors who believed in me and provided constant feedback on many drafts of all chapters. This critical feedback and intellectual engagement helped motivate me, knowing that my work was being read by people I admired and trusted and that they wanted to hear more about some things and less about others. Writing is a very lonely endeavor and we all “need a little help from our friends.” It is just one’s self at the beginning though, and the page on which you type your words, which is like making fresh tracks in the snow. It can be hard to trudge across an open bog or field not knowing if it will be worth the effort. It also helped that my laboratory members, my mentees, and my colleagues were supportive of me trying to do this, to write a book that was not in the main a scientific research project.

Aside from your work, what are some things you would like readers to know about you?

I feel lucky to be alive and to bear witness to this beautiful planet we share with millions of other species. I am so happy that I live in a time and in a place where I can be both a Geek and OUT! despite the fact that there is also much to be done to create a more sustainable, fairer, more just, and equitable world for all of us.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet but wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

Why is being gay worth discussing as it relates to your career?

Because social and political contexts help determine what paths in life are available to us—from romantic partners to careers. When you are a marginalized minority, there are fewer options—some are closed off because of bigoted customs, policies, and historical inertia. By realizing that my fate was more in my own hands than not, I was able to find fulfillment and ask questions that were a bit off the beaten path—I was less concerned about what others thought of the questions I was pursuing as a scientist and writer—and more concerned with the answers to those questions. This locus of self-confidence in how I do science relates back to my pride at simply being who I am, who I was born to be as a gay man, which has distilled in me an unbreakable spirit that has allowed me to navigate the slings and arrows of being an academic scientist.

What advice might you have to give for other aspiring writers?

Pursue your passion in terms of topic and pursue the act of writing like it is a job. The former inspires you to be able to do the latter. Writing is work and it can yield good days and bad days. You have to roll with both kinds of days.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

Well, my new book is going to be about a different way that we and other organisms experience the world—not through spices and vices—but through color. My experience as a colorblind person has led me down this path, just as my experience growing up as my father’s son shaped MOST DELICIOUS POISON. I also have some short stories planned that relate to the origins of psychedelic chemicals that other organisms (and even our own brains) make. Stay tuned for more!

Finally, what LGBTQ+ books/authors (and/or science books) would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

For new books: How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures by queer author Sabrina Imbler has captured my heart. How Birds Evolve by Douglas Futuyma (who happens to be gay and a colleague of mine at SUNY-Stony Brook) is also excellent.

For old books: Anything by Ursula K. Le Guin—although not queer, some of the characters and storylines are. I especially liked The Word for World is Forest, The Dispossessed, and The Left Hand of Darkness. An important book for me, early on as a young adult was Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman for so many different reasons—just read this bit and you’ll see why: “I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of The stars, And the pismire is equally perfect, and a grain of sand, and The egg of the wren, And the tree-toad is a chef-d’oeuvre for the highest, And the running blackberry would adorn the parlors of heaven, And the narrowest hinge in my hand puts to scorn all machinery, And the cow crunching with depress’d head surpasses any Statue, And a mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of Infidels.”

0 Comments