B.A. Van Sise is an internationally-known photographer and the author of the visual poetry anthology Children of Grass. His visual work has previously appeared in the New York Times, Village Voice, Washington Post and Buzzfeed, as well as major museum exhibitions throughout the United States, and his written work in Poets & Writers, the Southampton Review, Eclectica, and the North American Review.

I had the opportunity to interview B.A. Van Sise, which you can read below.

CW: Discussion of the Holocaust and religious intolerance.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

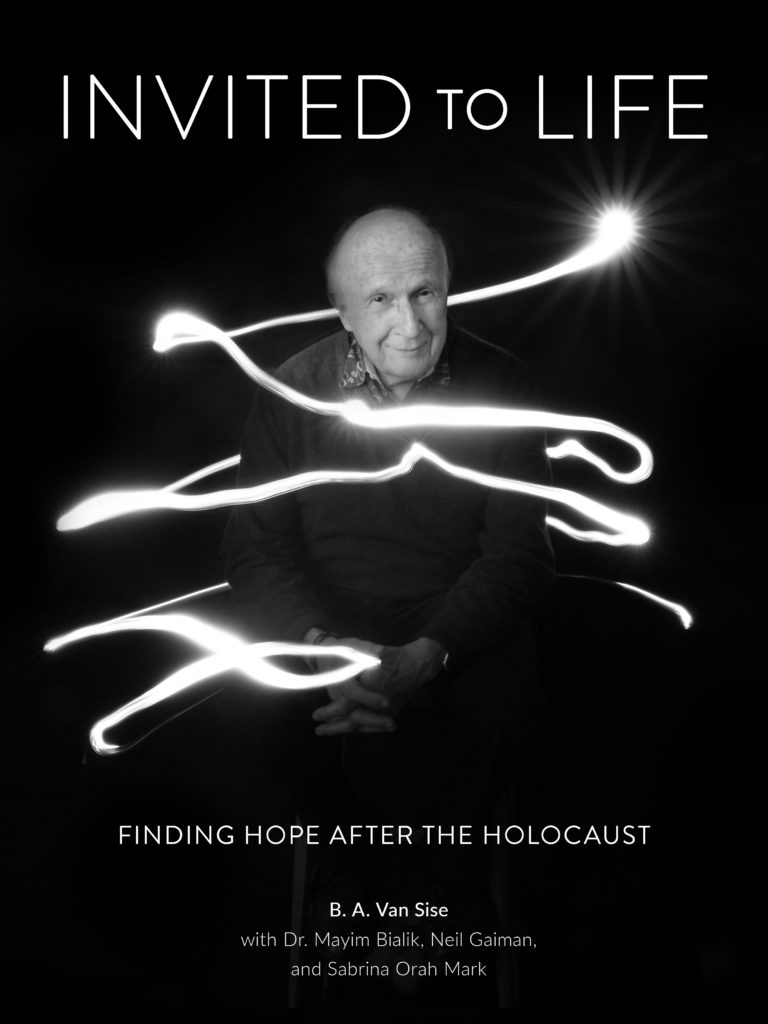

I’d tell you if I knew. I’m a photographer and author, the creator of two books: Children of Grass: A Poetry of American Poetry, and a new book, Invited to Life: Finding Hope After the Holocaust, which came out on January 27th! It’s a very large, somewhat complex book exploring the diverse journeys made by Holocaust survivors— whose existences were constructed on the worst foundations possible— to build new lives, new hopes, and new happiness in their American futures. It’s also got essays by Neil Gaiman, Mayim Bialik, and Sabrina Orah Mark, who are the only names Walmart puts on the tag.

I’ve been a travel journalist most of my adult life. I’ve been to 102 countries and have never met a stranger in any of them.

What can you tell us one of your latest works, Invited to Life: Finding Hope after the Holocaust? What was the inspiration for this project?

It began in late 2015; I was working as a photographer for the Village Voice, and at that time there was a guy running for president who was talking a lot about the supposed dangers of refugees, particularly Mexicans: there was a lot of rhetoric about how they’re not sending their best people, that we need to build a wall to keep us free. I asked my then-editor to let me do a spread to run that spring during primary season: I wanted to make a dozen portraits or so of refugees who had come to America, explore what their lives looked like once they could be seen in their whole. The folks who’d come in from the various wars in the 90s were still too young to really reflect on lives entire; the big wave of Cuban immigrants from the 1980s and 1960s (my original inclination, especially as I’ve done lots of work in Cuba) were not quite there yet. But I realised there was a huge wave of particularly “other” refugees, in Holocaust survivors, who’d come to the States penniless, broken, not speaking the language, of a religion alien to the majority, who’d still, against every odd, made their way over the following 75 years. They were the refugees, the “not their best people.” I wanted to show how that experiment had turned out.

At its core, it’s never been a Holocaust project to me: it’s about America. It’s about diversity of experience.

I reached out to the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, who helped me find survivors; I aimed for 12 and found it so meaningful that I ended up doing 37. It ended up as an outdoor show at the MJH and I then put it on a shelf. When the pandemic hit I was absolutely, totally ruined: of course, my main job had been as a travel photographer, and then shooting a few weddings a year. Travel was done! Love? Forget about it. I was feeling pretty sorry for myself, but my mind kept turning back to the survivors, almost obsessively- every one of them had gotten a worse deal than almost anybody in the current troubles. I wanted to hear, and see, and then tell, the stories of how these folks had not only survived but thrived. I worked with… most every museum related to the topic in the States, and then photographed the next hundred survivors, all over the country, through the pandemic. That was my pandemic: the Holocaust, in a Hyundai.

As a Jewish photographer, how would you describe the personal significance of this project for you?

I think there’s a natural inclination in modern times to require a personal angle to every project, but we also learn best, and most, when we learn from those who are most different from us. It’s complicated. I walked into this with no close personal connection to the Holocaust- and now I’ve got 140 of them. A lot of the survivors I’ve met, interviewed, photographed have become, truly, friends. With the book coming out now, I had lunch with one just today, in fact. I’m dropping in on five people in this very book next week. Right before it comes out, I’m going to dinner with the French survivor who has somehow, horrifyingly, turned into the lightning rod for much of the hate mail I get around this project. If there’s somebody I want to celebrate every day somebody has shot at me and missed, it’s her. These people have become very, very special to me.

Anyway, the personal significance for the project, to me, is this: I find these folks incredibly, unspeakably inspiring. I wouldn’t be able to process what they went through. If I’d gone through it, I’d not be able to feed or bathe myself. But here are folks who endured, who lived lives as diverse as they are: alone, accompanied, atheist, Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, gay, straight, wealthy, poor, honest, criminal. Artists and accountants, vagabonds, and the unjourneying, invited to life and choosing to live in every way imaginable, against all odds.

As an artist, what drew you to the art of photography, specifically portraits?

Greed. Unmitigated greed. Insatiable greed. By which I mean: I have a hard time defining what my job is, but I fundamentally look at my career as a conduit for my own personal kind of greed: I believe everybody you meet, absolutely everybody, has something to teach you. And this gig lets you meet absolutely everybody.

Now, I have a varied body of work- a person could argue I’m a portraitist, a writer, a street photographer. But all of them feed that same greed: again, everybody has something to teach me, and I want it. I want it so badly. I want as much of it as possible.

For those curious about the process behind a photography book, how would you describe the process?

The Book is kinda my ideal medium- I loooove doing exhibitions, but because my work is so inherently tied with language, the book is where it is, I think, purest. You’ve seen Invited to Life, so you’ve seen, surely, that it’s an eccentric book: it’s unfair to call it a photo book with text. It’s unfair to call it an illustrated book-book. If a person called it a book of poetry, nobody would argue with them. It’s not about the Holocaust. It’s not not about the Holocaust. There’s a lot going on.

I didn’t originally plan to do books, but while working on my first big-big-big project, about notable American poets, I photographed very last the poet Alicia Ostriker (an artist whose work should be frocked, at all times, by the eager readers of Geeks Out, whose Venn diagram with her is a perfectly overlapping set of circles.) She urged me to make a book of it and that’s how it goes: your whole life, you’re painted red, and then one day somebody breezes past you with a blue brush and you’re forever purple. When that project ended up getting turned into a massive, unbelievable, six-month solo show at the Center for Creative Photography- one of the most venerable photo institutions in the world, which will be at the close of my life still one of the greatest honors in it- everybody involved kinda said: “oh shit, there should really be a book.” And so, on an incredibly short timetable, the folks from the Arizona Poetry Center, a publisher named Schaffner Books out in Arizona, and 90 poets all got into cahoots to get the whole thing put together. It was really something.

With Invited to Life, it was different. By the end of the first shoot I did of the “new batch” (of Werner Reich, who opens the book with the pull quote of the century) I knew that other people needed to benefit from what was helping me through all of it. It was obvious- this was in the late summer of 2020- that we were all going to come out of this with awkward bends in our machinery. I wanted to put something together that would share lessons from folks who’d been through the worst but still could put their whole lives ahead of them.

We had the luxury of time; my agent, Charles Kim, got to shop it around a lot and there was a lot of interest. In the end, it came down to a very big famous publishing house- the sort of place that makes a writer’s knees wobble- and a smaller house in Pennsylvania, Schiffer Books. Schiffer specializes in illustrated books and I knew and had been impressed by them from a few titles they’d sent me to review over the years (I’m a reviewer for the New York Journal of Books, and they’d lobbed a bunch of stuff over my transom.) I knew they’d put the kind of attention to the book that I could really be proud of. And, well, you’ve seen it: they did a phenomenal job, in really adverse conditions: a pandemic, paper shortages, shifting tariffs, and other factors beyond their control. Generally, with books, there’s a lot of back and forth and bickering and creative egos and so on, but we didn’t have that; we fought over the title (they won), and over the cover (I won,) but their editors were great and their designers were amazing. And the book is BIG. It’s big and heavy and meaty. Rarely does one meet such an inspiring cudgel.

For the book, you included a variety of survivors and their loved ones, including images of multiracial families and queer survivors too. How did you go about finding the people you photographed for your project and your interactions with them?

It was very, very intentional; I believe, strongly, in the idea of a pluralistic America, a pluralistic future, and that’s where you really can feel me in the book. From the get-go, I wanted to include families of color, people with different lifestyles. I knew that survivors don’t fit the box the world wants to put them in– everybody’s seen the endless pictures of survivors portrayed as pathetic, weakened, hopeless victims. I know too many to not know better: their lives are as diverse as any other. I knew there were survivors whose family lives had stepped out of the traditional bounds of faith and ethnicity; I knew that there were surely queer survivors. And I knew they wouldn’t be hard to find.

They weren’t.

A fellow named Ari Goldstein- who was super helpful, and shares some of my thoughts on identity- stepped up and delivered really incredible, inspirational people: survivors who’d fought hard roads and had families that didn’t look like folks expect them to, lived lives that folks expect them to. This goes for faith, too: not all of the survivors are Jewish. Not many of the survivors are religious. I made a point, after my 72nd survivor was the first to mention God, specifically to deny his existence- to find survivors who, often because of their experience, did believe. There’s a million different paths to the life one wants to live.

What were the reactions like to Invited to Life?

All over the place. I get so many notes from people who thank me for sharing these survivors’ inspirational stories; I also get a fair share of hate mail- I’m apparently at the weird crossroads where White Nationalists, a more recent group I’ve come to call The Kanye People, and dextrocardial Jewish folks meet up. I get weird mail from people who- seeing my surname and making assumptions- call me a race traitor. I get weird mail from people who tell me I’m making up stories as part of some massive ill-defined Semitic conspiracy. And I get mail from religious and/or traditionalist people upset that Invited to Life contains people of color, LGBT folks.

I was really glad that the Center for Jewish History in New York was so eager to put it up this Spring/ Their institution houses a lot of different groups with different opinions, backgrounds, and they still put up the kind of show I hoped for: one that’s purposefully inclusive. But I’ve lost two potential exhibitions-one at a Holocaust museum, one at a museum focused on 20th century history- because they couldn’t allow my inclusion, specifically, of LGBT Holocaust survivors. Both said they’d easily be able to put it up if I’d just remove my portrait of two men embracing- the first museum was institutionally opposed, and the second had a sympathetic curator but a frowning board member with one hand clutching pearls and the other pursestrings. I make work to be seen, I tell stories because I want them to be heard. And I believe, strongly, that one should welcome a wide breadth of opinions, even and perhaps especially if they counter my own. But I couldn’t metabolize the thought of erasing queer people, people of color.

Growing up, were there any stories in which you felt touched by/ or reflected in, in terms of personal identity? If not or if so, how do you think this personally affected you as a writer?

Lots. I grew up in a storytelling family on both sides: my father’s people had a really very old lineage with a couple of famous people in it, a cool demeanor but a deep, deep sense of legacy. my mother’s people had spent centuries on the move, originally North African and then into Italy and had a very hot-blooded aspect to their character. There’s a richer story I could tell you, but honestly, when you asked this my mind first jumped to my father’s father: I don’t really remember him, just the faintest little bit, but his ghost loomed very large over our family. He had a car I never saw, a boat I never saw, a voice I can’t remember, a face I can’t remember, but I am absolutely certain –in my marrow– that I know him. But, of course, I also know that I don’t. At all. It really instilled in me the idea that there’s such a thing as not a person but the idea of a person, as not a place but the idea of a place. No matter how much you construct them, no matter how much you define them, they’re never real.

As a photographer, who or what would you say are some of your greatest creative influences and/or sources of inspiration in general?

I read more poetry than anybody you know. I look at a lot of paintings, a lot of sculpture. I actually don’t peruse a lot of photography, funny as it sounds. That’s not exactly my influence. Coming up, I interned for a while with Arnold Newman (as famous a portraitist as ever there was) but I learned nothing from him but that one can- and often should- be disappointed by their heroes. Truth be told, more of my work comes from my love of poetry, and from my childhood fascination with prestidigitation. I joined the International Brotherhood of magicians at the age of 14 (and am still a member)- but legerdemain is not my domain. I’ve not turned a card in decades, or palmed a coin in just as long. I put that instinct, instead, into photographs.

What are some of your favorite elements of photography? What do you consider some of the most frustrating and/or difficult?

There’s a cliché in the world of professional poker: the great players are constantly besieged by people wanting to tell them their “bad beat” stories. Some players rudely decline, some turn a deaf ear until it’s over. For me, the worst element of photography is people talking about their gear. Writers don’t compare their word processors, nor pianists their Steinways. I truly believe this: when Woody Guthrie put “this machine kills fascists” on his instrument, the guitar was not the machine he meant.

My favorite element of photography: I have an aunt who, when I was a kid, would make us watch very long slideshows of whatever she’d done in the last few weeks whenever we went over. We were always bored to tears, but she treasured those photographs like they were all worthy of Pulitzers. And that’s correct: photographs- like poems, and children, and lots of other things- always look a little better when they’re your own. Photography lets you make new babies, every day.

Aside from your work, what are some things you would want others to know about you?

I’m allergic to grapefruit. Tell the waiter.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet but that you wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

Two: nobody’s asked me who I wish I could’ve included: Dr. Ruth! She said yes and then changed her mind, due to covid. And George Soros. He’s probably the most famous Holocaust survivor alive in America today, though imagine the mail I’d get.

The second I don’t have an answer for, but if somebody wants to tell me I’m all ears: I wrapped the photography for Invited to Life in April of 2021, wrote it in late summer, and the delivery of Neil’s essay in September of that year finished the book. From that moment to this, 23 of the 90 survivors in the book have died. What does this work look like when they’re all gone?

What advice might you have to give for aspiring artists?

The same advice they give young priests: if you can do anything else, do that. It’s a tough life. But! I have the thinnest acquaintance with the art critic Jerry Saltz, and enjoyed something he said recently: that the art world is, in a lot of ways, like a gang. Blood in, blood out. If you’re in, you can’t leave. You can never, happily, settle into doing anything else. You’re in it, forever, and you need to understand that going in.

Are there any other projects you are working on and at liberty to speak about?

I write a lot. I wrote three chapbooks of poetry and one full length book last year, of which I’ve not so much as even put them in front of my agent or any publisher. But the thing I’m most proud of is a project I started in mid-2021 (now about halfway done) about the poetry inherent in America’s endangered languages. It’s called On the National Language: the Poetry of America’s Endangered Tongues– named after the first line of a colonial-era law written to protect minority languages- and it’s been an amazing, amazing experience. Have been traveling all over the country, working with speakers of all these languages (many of which come from minority and marginalized communities,) giving them a place in their own representation (something not often afforded, historically, if we’re honest) and most importantly: it’s just cool. It’s really. Freaking. Cool. Poetry in motion. I spent a week on an Amish guy’s farm, milking his cows and talking about the ways his daughter’s language is different from his. A Louisiana Creole lady taught me songs and made me drink tinctures. And I did a shoot with a speaker of Nahuatl out in Los Angeles the other day, and there’s a single word in that language that means you are bursting into bloom all over with stars like flowers. Everybody has something to teach you. There’s so much to learn.

Finally, what books/authors/photography would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

Let’s see- what have I seen lately that I’ve loved?

Poetry: Shelly Puhak’s book of poems, Harbinger, and Mosab Abu Toha’s Things You may Find Hidden in my Ear. I’m excited for Janine Joseph’s Decade of the Brain, Gabrielle Bates’ Judas Goat, and Jane Hirshfield’s The Asking, which aren’t yet out but which I’ve gotten to see through the sonogram of criticism.

Prose: He’s surely familiar to your readership, but I’m low-key obsessed with Taylor Brorby’s Boys and Oil. We were paired on a story a few years back and I’ve really enjoyed watching him bring such a stunning gift into the world.

Photography: Lately, I’ve really been enjoying Ann Prochilo’s This is Water, which I saw at a show at the Los Angeles Center of Photography last month. Also Mitch Epstein’s Recreation, and just generally Kurt Markus, who just died, the cake of whose life can be defined by no one crumb.

0 Comments