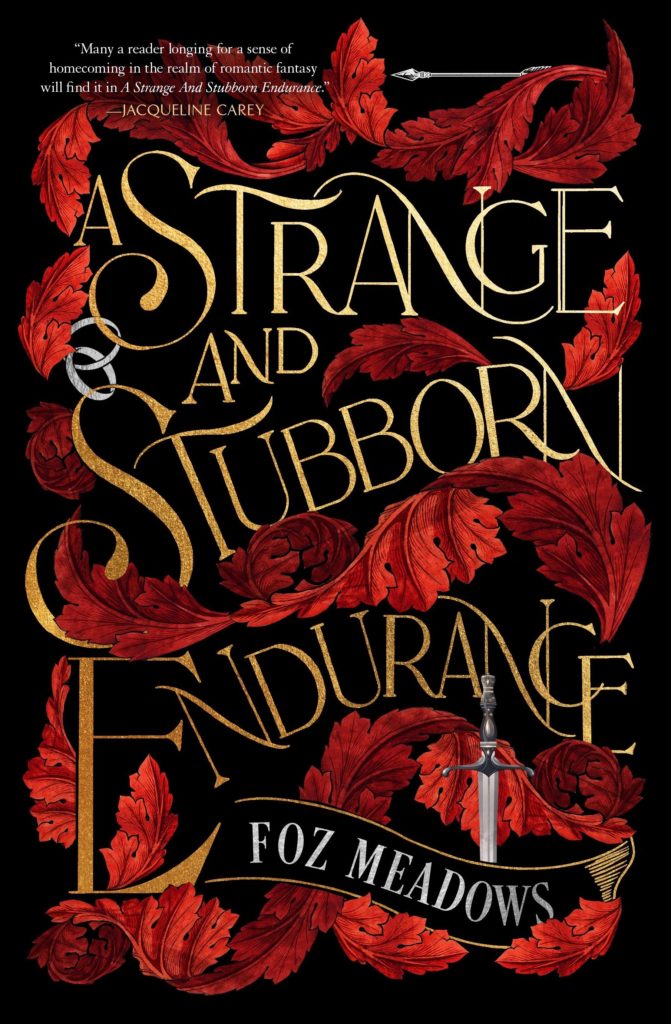

Foz Meadows (all pronouns) is a queer Australian author, essayist, reviewer, and poet. She has won two Best Fan Writer awards (a Hugo Award in 2019 and a Ditmar Award in 2017) for yelling on the internet and has also received the Norma K. Hemming Award in 2018 for her queer Shakespearean novella, Coral Bones. Her essays, reviews, poetry, and short fiction have appeared in various venues, including Uncanny Magazine, Apex Magazine, Goblin Fruit, The Huffington Post, and Strange Horizons. Foz currently lives in California with her family. A Strange and Stubborn Endurance is her fifth novel.

I had the opportunity to interview Foz, which you can read below.

CW: Discussion Of Abuse And Sexual Assault

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a little about yourself?

Thank you for having me! I’m a bi, genderqueer Australian SFF writer currently based in California, though I also lived in the UK for five years. I have a queer portal fantasy duology out with Angry Robot – the first volume, An Accident of Stars, is getting reissued in June! – and my newest book, A Strange and Stubborn Endurance, an m/m fantasy romance, is out from Tor in July.

What inspired you to get into writing, particularly romantic speculative fiction? Were there any writers or stories that sparked your own love and interest in storytelling?

I grew up in a house full of books with parents who wrote for a living, so it’s no surprise that I started making up stories a very young age. I gravitated pretty quickly to all things fantastic and mythological, but I didn’t really figure out my relationship with romance until I was an adult. Hollywood romcoms frustrated the hell out of teenage me, but I loved the romances I saw in Austen and Shakespeare; it wasn’t until I started learning about things like tropes, sexism and heteronormativity that I understood where the disconnect lay and why. I started reading straight romances – some historical, some urban fantasy – because they were what I could access at the time, but what really made the genre click for me was fanfiction, not just because it was overwhelmingly queer, but because the act of seeing tropes labelled and leaned into was a series of lightbulb moments. It was as if I’d been eating a series of desserts, only some of which I enjoyed, and trying to identify which ingredients worked for me by taste alone, and then someone came along and gave me a recipe book. Like, oh, I see now: I like mutual pining, but not if it’s paired with cartoonishly forced miscommunication, which explains why I enjoyed story A, but not story B. And once I’d written enough fanfic of my own to feel confident that I loved writing romance as much as I loved reading it, the next logical step was to pair it with SFF!

What can you tell us about your upcoming book, A Strange and Stubborn Endurance? What inspired this story?

A Strange and Stubborn Endurance is an arranged marriage romance between Velasin, a gay man from a homophobic culture, and Caethari, a pan man from a queernormative one, that deals with trauma, healing, autonomy and political intrigue. On one level, it’s a purely self-indulgent book: I initially started writing it for fun back in 2015 when I was briefly between deadlines, because it was the kind of thing I wanted to read. But the more I wrote, the more personal it became. I’ve read a lot of great stories about queer people finding love within or despite their bigoted societies, but particularly in the case of queer historicals, I always have a sort of latent ache for the characters, even when they get happy endings, because they still have to navigate prejudice and secrecy in the wider world. And as much as I also love SFF stories with purely queernormative settings, sometimes you want both the grappling with queerness as a necessarily political identity and the happily ever after in a world that accepts you, because that messy combination is, for many of us, the one most true to real life. We might grow up in a homophobic household or just an unhelpfully heteronormative one, figuring ourselves out in any number of ways – fearfully, defiantly, piece by piece, self-destructively or as an act of healing, or perhaps both at once – until we find our place and our people, which might be on the other side of the country, all the way across the world, in the next town over or right where we’ve always been, but seen through new eyes. Even when we become queer revolutionaries, it’s not the first thing that most of us aspire to: we just want to be ourselves, which means first having the freedom to figure out what that means, and so we end up fighting out of necessity and kinship and a basic desire to be treated as people, not because we’re all naturally ornery (though of course, as with any group, some of us are), but because the alternative is abnegation.

And so I wrote Velasin: a man who grows up hiding his identity, who suddenly finds himself in a nation that accepts his queerness, but under traumatic, emotionally fraught circumstances. There’s all these wider political implications to his marriage that he has to navigate – and those are further explored in the sequel, which I’m currently working on! – but at the same time, he still gets hung up on things like I didn’t realise I could hold my husband’s hand in public, or the whole idea of marriage as I understand it is based on heteronormative gender roles, so what am I meant to do, actually, as a husband’s husband? And meanwhile Caethari, by virtue of having grown up in a different, more accepting context, can’t always get a read on what Velasin is thinking, because he doesn’t have the same hangups. So they have to work to understand one another – and to stay alive, because see above, re: political implications – while also figuring out what’s going on, in a way that both is and isn’t about navigating queerness.

This book was said to be written with the intention of creating a story that centers queer joy and queer thriving in the wake of trauma. Could you expand on that, please?

To try and answer this question properly, I’m going to talk first about the trauma, and then about the thriving. So, this is a slight spoiler – there’s a trigger warning for it at the start of the book, and it happens very early on, but skip this paragraph if you’d rather go in unprepared – but after Velasin is betrothed, his ex-lover shows up and assaults him; they get caught together, but the act isn’t recognized by the witnesses as rape, and this is how Vel is outed, which is what causes the visiting envoy to say, well, if you don’t like women, that’s fine, you can marry a man instead. Which is obviously horrifically traumatizing for Velasin: not just the rape itself, but the betrayal it represents and the fear it engenders around his marriage. I’ve seen a couple of reviews describe the scene as graphic, and obviously that kind of content will hit everyone differently, but to me, it’s foremost about psychological hurt, not brutalization – a sort of literalised metaphor for cultures of shame and silence around sexuality. In a context where even consensual sex is stigmatized, how do you report an assault? This is a fundamental issue of rape culture, and it applies equally to members of the queer community as to straight cis women. When visible, violent damage is considered the only real “evidence” of assault, a different kind of violence is done to the victim: you weren’t hurt enough where I can see it, so therefore you weren’t hurt at all. And when the relevant authorities are more critical of the victim’s sexual identity than the perpetrator’s motives, there’s no real way to get justice, which is what Vel is dealing with at the start of the book: he can’t say he’s been assaulted, because his queerness is considered the greater crime.

But then we go from Vel’s homophobic home nation to the queernormative culture next door, and we see what queer thriving can look like. Caethari is a big part of that – not just because of his kindness to Vel, but in the contrast between their lived experiences. Cae has grown up accepted for who he is, able to love and liaise as he pleases, and as such, he has healthier expectations of a world that loves him back. His whole concept of marriage and family is fundamentally different to Vel’s by virtue of not being tied to heteronormativity: his sister and her wife, for instance, are in the process of negotiating paternity for the child they plan to have, and that’s just a normal part of life. So when they first meet, Cae is frustrated that Vel doesn’t seem to want to work with him towards a successful marriage: he has no framework for how alien the notion is to Vel, even without his recent trauma. But once he earns Vel’s trust and the two of them start to cooperate, we see Vel begin to process the differences between how he was raised and the place he is now, and what that means for the person he wants to become. It’s hard to say more about that aspect of things without deeper spoilers, but Vel’s arc is very much intended as a healing one, and I hope I’ve done it justice.

What are some of your favorite elements of writing? What do you find to be some of the most challenging?

My favourite part of writing is when I get into a groove: I can see everything laid out in my head, the exact trajectory from where I’m picking up the story to a given emotional endpoint, and it all flows out like water poured from a cup. When that happens, it’s the best feeling in the world: any time I break to eat, I’ll be rushing through it, eager to get back to the story, and hours will pass in a flash because I’m genuinely enthralled. By contrast, the most challenging bits are, inevitably, the places where I get stuck. The way my brain works, it’s like I’ve got an underlying instinct for how the story works, but I can’t always access it consciously, so when I start to go the wrong way, the subconscious brain throws up a red flag – “Stop!” – without actually telling me why. So I’ll be sitting at the keyboard thinking, Wait, what’s wrong, why can’t I write this scene? And my brain just goes: Can’t. And so I have to go away and do something else until I figure out what the problem is.

Link scenes, or what I think of as link scenes, also tend to be a slog, because they’re deceptively tricky: little stretches of description or dialogue that tie everything together and steer the narrative along without actually being emotionally load-bearing. They’re often some of the most quietly important bits in a book, because getting them wrong can leave the reader thinking the story doesn’t make sense – wondering why the characters didn’t communicate properly, for instance, or why a certain action is happening now instead of later, or how the plot logic works – but when you get them right, they’re invisible.

In addition to being a writer, what are some things you would want readers to know about you?

Functionally, I am several raccoons in a trenchcoat, and would describe my general level of online-ness as somewhere between internet poisoned and terminal. I have a nine-year-old son and three cats, and I’ve thus far enjoyed nearly fifteen years of marriage to a professional logician, which is a subgenus of philosopher who does maths about existence. This means I have spent more time in pubs debating nonsense with drunken academics than is strictly healthy, which possibly goes some way towards explaining how and why I’ve spent thirteen years on the cursed bird app without throwing my phone in a lake. Also, I’m a little obsessed with the k-pop group Stray Kids. Their latest album is amazing.

What advice would you have for aspiring writers, especially other queer writers?

Literary trends begin with agency wishlists and end on bookshelves, not the other way around: by all means, take inspiration from what’s being published, but if you’re aiming to capitalize on or be part of the next big thing, look at what agents are collectively interested in acquiring now, not what’s already selling in stores. That being said, I think it’s best to write for yourself first – and that means any version of yourself: the person you were, the person you are, the various people you might become – and for other people second. You also need to remember that it’s impossible to please everybody: that there’s no such thing as the perfect book, only the perfect reader. Which doesn’t mean that it’s pointless to do the research, or to think carefully about whether you’re the best person to tackle a given narrative, or to develop your craft as a writer – all of those things matter. It just means that you have to be judicious about the criticism you accept and the criticism you ignore; to decide whose opinions matter to you, and why, and to carry that energy with you into your dealings with the wider publishing industry.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet, but wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

I can’t really think of a specific question, but I would like to say that the last two years have been really hard for just about everyone. We’re living through a period of intense global trauma, so even if you personally haven’t lost someone to the pandemic or been sick with COVID or struggled to find work, this is your reminder to be kind to yourself, because the constant stress and anxiety have still been impacting us all.

Are there any other projects you are currently working on and at liberty to talk about?

Aside from the sequel to A Strange and Stubborn Endurance, I’ve got two other epic fantasy drafts on the backburner: one is about an apprentice monster vet-slash-zoologist getting embroiled in politics, and the other is an angry sort of murder mystery romance in a setting where mages get their power from being touched by gods. I’m really excited about both of them, and I hope I get to share them with you eventually!

Finally, what LGBTQ+ books/ authors would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

There’s so many awesome queer books out right now, but some standout recent favourites are Summer Sons by Lee Mandelo, She Who Became the Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan, The Jasmine Throne by Tasha Suri, and the Broken Trust series by Juliette Wade, which begins with Mazes of Power. Check them out!

0 Comments