Raymond Luczak (he/him/his) is the author and editor of 29 titles, including Flannelwood: A Novel (Red Hen Press) and Silence Is a Four-Letter Word: On Art & Deafness (Handtype Press). His book once upon a twin: poems (Gallaudet University Press) was a Top Ten U.P. Notable Book of the Year for 2021. His work has appeared in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere. An inaugural Zoeglossia Fellow, he lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. You can follow him on Twitter or through his Facebook page.

I had the opportunity to interview Raymond, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT! Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

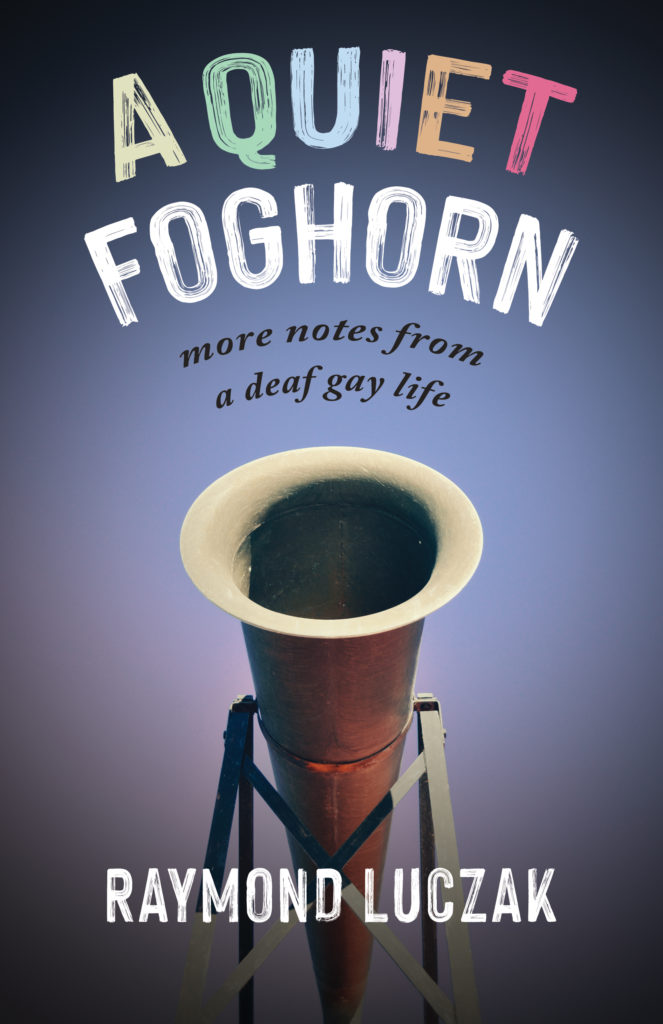

I’m a Deaf gay writer and editor of 29 titles, including my latest book A Quiet Foghorn: More Notes from a Deaf Gay Life (Gallaudet University Press). I lost most of my hearing at the age of eight months due to double pneumonia and a high fever, but this was not detected until I was two-and-a-half years old. After all, I was just number seven in a hearing family of nine children growing up in Ironwood, a small mining town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (U.P.). Forbidden to sign, I was outfitted with a rechargeable hearing aid and started on speech therapy immediately. After graduating from high school, I finally learned American Sign Language (ASL) at Gallaudet University.

How would you describe your upcoming book A Quiet Foghorn? What was the inspiration for this project?

When I put together my first essay collection Assembly Required: Notes from a Deaf Gay, I had chosen not to include a number of arts-related pieces that had appeared over the years. This time around I wanted to pull the various threads of my interests—the arts, the political, and the personal—into a single book. By then I had amassed more published pieces, so it made sense to include most of everything this time around.

As a gay D/deaf writer, you write on the intersection of queerness and disability. Was identity something you had always intended to explore within your writing, or was it simply a natural evolution? At any point during your life have you found media (i.e. books, film/television, etc.) in which you could see yourself reflected or relating to in terms of personal representation?

It was not necessarily intentional at first, but it became a necessity once I realized that there weren’t any accurate representations of the Deaf gay experience in literature. It was quite obvious that if no one was doing anything about that, I might as well try my best and write about it. You could say that’s been the story of my career. If I couldn’t find anything similar to my experiences in print, I felt obligated to write about them, starting with my Christopher Street magazine essay (“Notes of a Deaf Gay Writer”) in 1990 and continuing with my editing Eyes of Desire: A Deaf Gay & Lesbian Reader (Alyson), which turned out to be the very first published title exploring the Deaf LGBTQ experience in the world back in 1993. I haven’t stopped since!

How would you describe your writing process? What are some of your favorite/most difficult parts of the creative process for you?

Each piece I write rarely starts in the same place. Inspiration can be found anywhere. It’s best if I don’t think about it too much. Just roll with it and see what happens when I write! I like discovering new things in my work after I’ve written the first draft (and rewritten in subsequent drafts) because it’s almost as if I didn’t really know my inner self was thinking while writing!

What’s something about deafness you might want someone to take away from this interview?

That silence, particularly when it pertains to the Deaf experience, is a metaphorical cliché that needs to be permanently iced on moratorium. Very few Deaf people have total hearing loss; they can hear some things at certain frequencies and volume, and yet cannot hear other things. Just like there’s a spectrum when it comes to sexual orientation, there too is a spectrum for hearing loss. Reducing Deaf people to just their ears and/or their signing hands regardless of where in the media is incredibly reductive and offensive to the Deaf community. We are not your metaphor. We are so much more vital than that! We are a people, a community.

Besides your writing, what are some things you would want readers to know about you?

I love to make ice creams and sorbets!

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet, but wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

I’d love to have hearing people ask themselves this question: Why do I expect Deaf people to carry the full burden of communication when I interact with them? In other words, hearing people have always expected me to lipread, and they’re too happy to find out that I can speak. And then they get occasionally frustrated if I cannot lipread them well enough, and end up saying, “Never mind,” which ends the conversation. (For the record, even the best lipreader in the world can catch maybe 30% on the lips if they don’t know the context of the conversation.) That line (or variations thereof)—“Never mind”—is extremely demoralizing because I’ve taken sixteen years of speech therapy, but they couldn’t be bothered to try another way to rephrase so I can understand them better? When they say, “Never mind,” they are telling me that their discomfort with the situation is much more important than my desire to fully understand what is going on, and therefore, they are exercising their hearing privilege over me. They do not want to put in the same effort into the conversation that they’ve expected me to do. Communication is a two-way street, and contrary to what the majority would like to believe about us Deaf people, it is not run by hearing people. It is run by both people in the conversation.

What advice would you give for other writers?

Never, never, never give up. Rejection is normal, so you have to learn not to take it personally. I’ve had editors reject my work a few times only to accept this or that piece. (Part of that may be due to luck and/or timing.) It’s more important to keep writing, rewriting, and reading the work of other writers who are better than you so you can improve your craft.

Are there any other projects you are currently working on and at liberty to speak about?

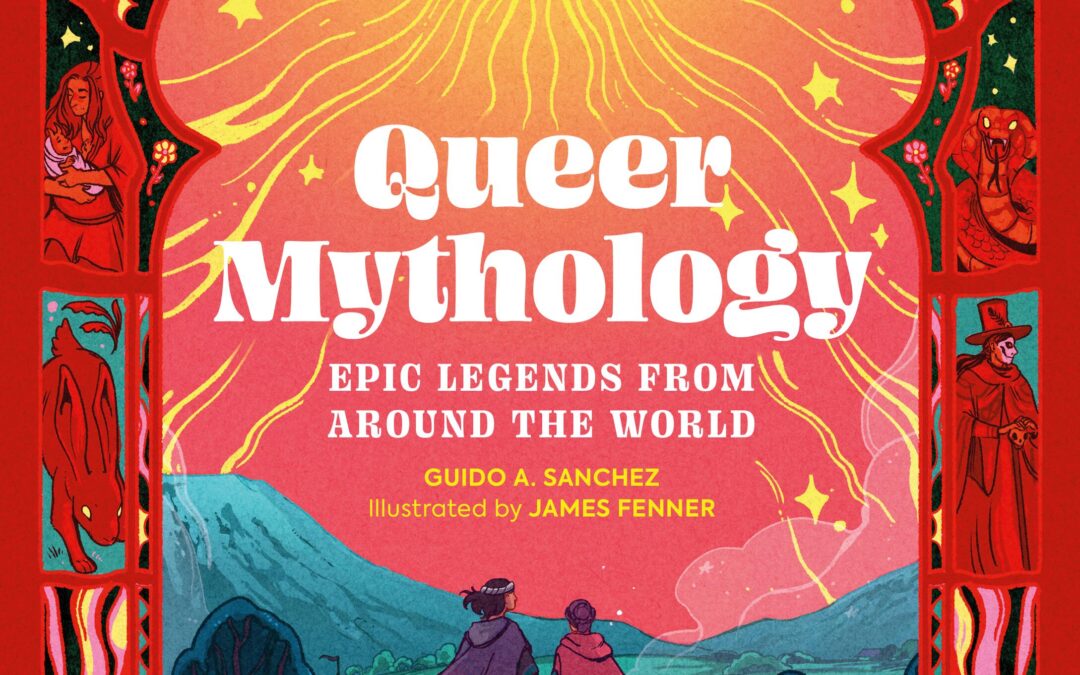

2022 has been a very busy year. Two of my full-length poetry collections have appeared in print recently: Lunafly: Poems (Gnashing Teeth), which is filled with queer retellings of Biblical stories, Greek myths, and paganisms, and Chlorophyll: Poems about Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (Modern History Press), which is a sequel of sorts to my earlier childhood nature poetry collection This Way to the Acorns: Poems (Handtype Press), but this time from an adult’s perspective. These days Rattling Good Yarns Press is finalizing my next novel Widower, 48, Seeks Husband for publication. While the novel covers some 40 years of gay Minneapolis history, the book explores in depth what it means to be a middle-aged gay widower in a community that can be unfortunately lookist and ageist. It’s not necessarily a book for young queer reader; it’s a story written for older gay men who’ve been around the block and then some. The story was partly inspired by my realization and disappointment by how many gay fiction titles often featured young good-looking men on their book covers. Where are all those stories featuring middle-aged gay protagonists? (Andrew Sean Greer’s satirical—and commercially successful—novel Less [Lee Boudreau Books] is definitely an outlier in this regard.) It’s my hope that Widower, 48, Seeks Husband will come out this later this year; if not, definitely next year. As always, I do post from time to time ASL translations of my poems as well as book trailers on my YouTube channel here. [youtube.com/deafwoof]

Finally, are there any books, particularly books about disability/Deafhood, you would recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

Aside from my own collection QDA: A Queer Disability Anthology, which I edited for Squares & Rebels, I’d recommend Corbett Joan O’Toole’s Fading Scars: My Queer Disability History (Reclamation Press), Carol Padden’s Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture (Harvard University Press), and Harlan Lane’s When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf (Vintage). One should also check out the documentaries Through Deaf Eyes and Signing Black in America.

0 Comments