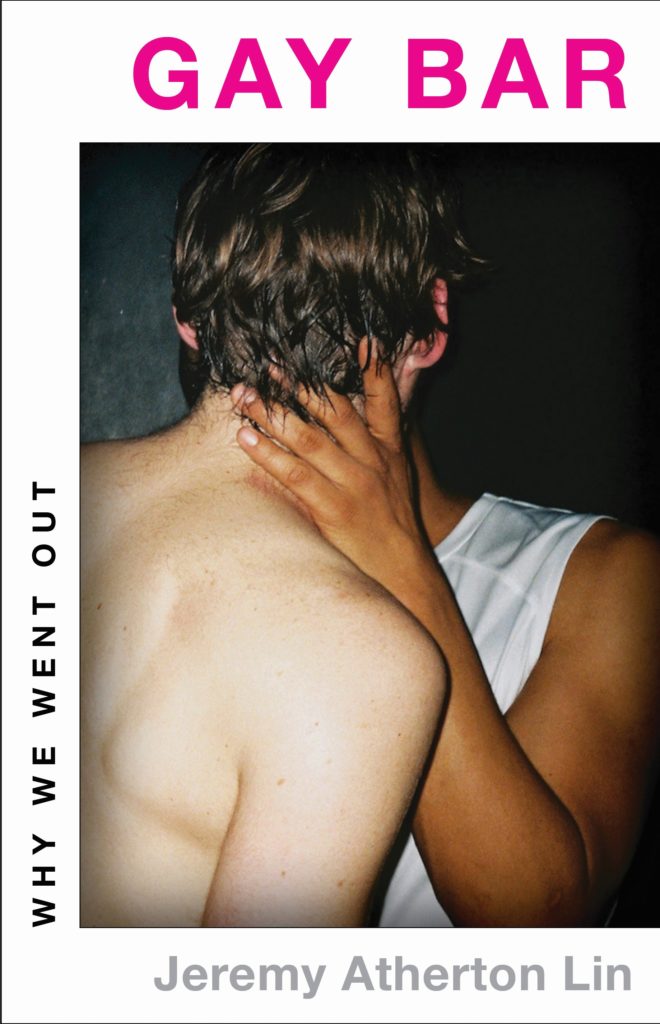

Jeremy Atherton Lin is an Asian-American essayist based in the UK. He has contributed to The Yale Review, Noon, Granta, The White Review, ArtReview, Literary Hub, Port, The Face, W, Tinted Window and the Times Literary Supplement. His debut book Gay Bar (2021) was selected as a New York Times Editors’ Choice and the Guardian Book of the Week. Jeremy’s mixtapes can be heard on NTS Radio, Spotify and Mixcloud. He has also appeared on NPR, BBC Radio London, BBC Radio 4 and Resonance FM. Teaching and speaking engagements include The Courtauld Institute, Cornell University, Central St Martins, the Royal College of Art, Camberwell College of Arts, University of Glasgow, Birkbeck University and the Edinburgh International Book Festival. He is an editor at Failed States, the journal of art and writing on place.

I had the opportunity to interview Jeremy, which you can read below.

First of all, welcome to Geeks OUT and congratulations on your debut book, Gay Bar! Could you tell us a little about yourself and the book? How did you find yourself gravitating toward this specific topic?

Thanks so much for having me. Sorry I’m late! I’m Jeremy, from California and currently living in London. My favorite color is pale lilac. I love pickles, okra and nectarines. I write, and teach sometimes, always seem to be running errands, and ride a rusty Dawes Galaxy that my next door neighbor gave to me.

With Gay Bar, I revisited spots where I’ve hung out over the years in an attempt to interrogate the connection between place and identity. I conceived the book around 2017, when over half the gay bars in London had closed within a decade. So this got me thinking: What does it all mean? Should we unequivocally lament the closure of these venues, or is it possible their time was up? Why should my identity be dictated by a commercial aesthetic and particular form of socializing? Had gay bars informed me, and how? With each bar in the book, I dug deep to figure out what went on before my time there, uncovering euphoric and problematic histories, dating to the 1970s and as far back as the 17th century.

When it comes to gay bars, what often comes to mind is “gay men” rather gay men and women, or queer people in general. Why do you think that is?

One reason could be that, in very general terms, women have often socialized in private spaces. In the States, for instance, there is an incredible history of house parties in locations like Oakland and Fire Island. Some early lesbian-run bars were known as much for other aspects, like poetry readings and live folk music. Commercial gay venues were generally dominated by white men. Now, of course, the most exciting parties may be those that center womxn, femmes and trans people of color. But my choice to write specifically about gay bars populated by men was deliberate — I was interested in rethinking a somewhat passé institution.

While the historical and symbolic significance of gay bars can’t be denied, there is something to be said about how gay bars have not always felt accessible to various members within the queer community, including the disabled/neurodivergent members of our community and others. How do we reconcile the idea of this queer safe space and its limitations?

It’s hard for me to think of gay bars as safe spaces at all — in that they rely on the consumption of booze, usually neglect to provide adequate wheelchair access, are lookist and ageist and have been blatantly racist and sexist, too. It was never my intention to write about what gay bars should have been or could be, but rather to consider what they have been, including the failings.

As a queer woman who’s also asexual, I’ve found that bars (gay or straight) haven’t exactly felt comfortable for me, since most contain an element of hook-up culture. Do you find the gay bar to be inherently sexual in nature or is the answer more complicated?

Oh, yes, the answer is always more complicated, right? Bars, after all, are commercial spaces, and sexuality of course has been repurposed as a weapon of commerce. Bars and other institutions of gay culture were selling sex even at the height of AIDS infections — they just sold an idea of sex, of its promise, and not just a promise of getting laid but of power and status. But in terms of my own approach, I was absolutely interested in gay bars as a site in which to cruise and engage in semi-public sex. I wanted the book to be as much about sexual proclivity as cultural identity, and about the tension between.

This book seems be a reflection on the past (both your own personal experiences as well as the collective memories of the queer community). As a writer, how did it feel exploring the lines between non-fiction writer/essayist and historian?

I would not claim to be a historian. I am, however, very interested in history as one strategy of learning, including the foibles of historical retelling. I gave myself the title of essayist in my twenties as a kind of risk, as if on a dare, and that’s how the job has remained — all about trying things out through writing. To essay, as a verb, means to attempt.

I sometimes say that I’m an unreliable narrator of non-fiction. Why do we expect our fictional characters to be flawed and complicated in order to appear ‘real,’ yet demand non-fiction authors achieve some kind of neutral and all-seeing stature? Writing Gay Bar, as I searched my memories, it was very much through the lens of my specific positionality — as Asian-American, gay, cis, West Coast, and so on. So I’m not going to bury any of these aspects, but lean in. And as I researched the historical elements of the book, I found various events — and the ways they were reported — to be delightful, funny, icky, repulsive, depressing, sexy, everything. I’m not inclined to hide my impressions of what I’m seeing. I reveal my point-of-view by selecting the very stuff that I find the most delightful or repulsive or whatever to share with the reader, because I want us to go on an intense journey together. And I can never be an objective guide.

What have been some of your favorite gay/queer bar experiences?

Those moments when I realized I’m dancing in a fire trap, but still can’t resist the beat.

In the time of Covid-19, has there been any cognitive dissonance about writing about a subject that has been shut down for so long?

I had mostly finished the book before the pandemic, but the interviews have been conducted throughout lockdown so yes, there was a kind of estrangement. On a personal level, I’m pretty adaptable. I began making radio shows as a way of communicating with others under the new conditions. And I’m very lucky to have a roof over my head, and a partner with a sunny disposition, so we approached much of lockdown as if it were a two-person house party.

In an article from i-D, “the gay bar is dead: how the queer space killed it” the author writes about the shifting cultural perspective on bars and how the gay bar may be losing significance in terms of other queer people finding alternative spaces to celebrate queer identity. What’s your take on this and your take on the future of gay bars?

I think these kinds of spaces have been, at their best, about exploring the possibilities within oneself and between others, rather than arriving into one uniform thing. And as everything continues to evolve, the ways we explore need to change, too. So the advent of new forms of coming together seems absolutely as it should be. However, that doesn’t mean I believe there’s no longer a need for the old school gay bar. For one thing, some elder lesbians, gay men and trans people might happen to like perching on a barstool in a comfy old dive, and I hope they continue to have destinations that afford them that kind of refuge.

What’s a question you haven’t been asked yet, but wish you were asked (as well as the answer to that question)?

“Which Sex and the City character are you?” Answer: I’ve never watched Sex and the City.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers, both those working on their craft and looking to be published?

Make playlists and mixtapes. For me, fostering musical arcs and a logic of transitions is akin to the nuts and bolts of storytelling. So that’s my advice on craft. As for getting published, I’d say worry first about the integrity of what you’re making. My own trajectory has been long and full of detours, but I was learning and improving. Then when the time comes, try sending short, polite emails to the agents who represent other writers you admire. Be precise, humble and open. Bring your sense of humor. Be prepared to listen. And remember: Be brief.

Finally, what queer books would you recommend to the readers of Geeks OUT?

I’m going to recommend a book that isn’t explicitly queer, but to me has a kind of queer undercurrent: The Mountain Lion by Jean Stafford. The young girl at its heart is prickly, dissatisfied and non-conforming. She’s perceived by others as unlikable, but she’s struggling to make sense of a sick world. Many, if not all, of the same things could be said of another of my favorite books, Cruddy by Lynda Barry. I am recommending them because they are about being messy. And I identify as a mess as much as anything.

0 Comments